How Charleston Has Become a World-class Culinary Capital, Travel + Leisure, January, 2018

by: Sid Evans

Forget the city of old, or even five years ago. A new wave of restaurateurs, designers, and hoteliers have put the jewel of the Lowcountry on the global stage.

When I was considering a move to Charleston to edit a new magazine called Garden & Gun in the summer of 2007, my wife and I went to McCrady's restaurant, just off East Bay Street, which was helmed by a young chef named Sean Brock. Having been spoiled by New York restaurants, we weren't expecting much, but it was hard not to be charmed by the entrance on a tiny cobblestoned alley, the long walnut bar, and the brick arch that framed the entrance inside. We couldn't get a babysitter, so we stashed our sleeping six-month-old daughter under the table in her car seat, praying that she wouldn't wake up and spoil a rare date night. Then the courses started coming — house-made charcuterie, sous vide scallops seared a la plancha, and something called country ham cotton candy. Here we were in a building that dated back to 1778, where George Washington once dined, and this mad-scientist chef was serving some of the most innovative, delicious dishes we'd ever had. For a couple debating a new life in an old city, that meal was a promise of exciting things to come. Our daughter slept peacefully through dinner, and by the end of the night (and after plenty of wine) we had decided to make the move.

Looking back, I realize that Brock was a messenger from the future — a devoted student of the region's culinary history as well as a brash, tattooed innovator. Within a few years he would be named Best Chef in the Southeast by the James Beard Foundation, and soon his tribute to Southern ingredients, Husk, which opened in 2010, would pave the way for an explosion of new restaurants and bars that would transform the city. Charleston is an international food destination now, like Paris or San Sebastián, Spain. You can't walk half a block without stumbling on some inventive new oyster bar, café, or barbecue joint, not to mention a Mediterranean standout like Stella's, where the calamari and keftedes draw a devoted lunch crowd, or a charming French bistro like Chez Nous. Eating is a sport there, a topic of conversation from the streets south of Broad to the suburbs of Mount Pleasant.

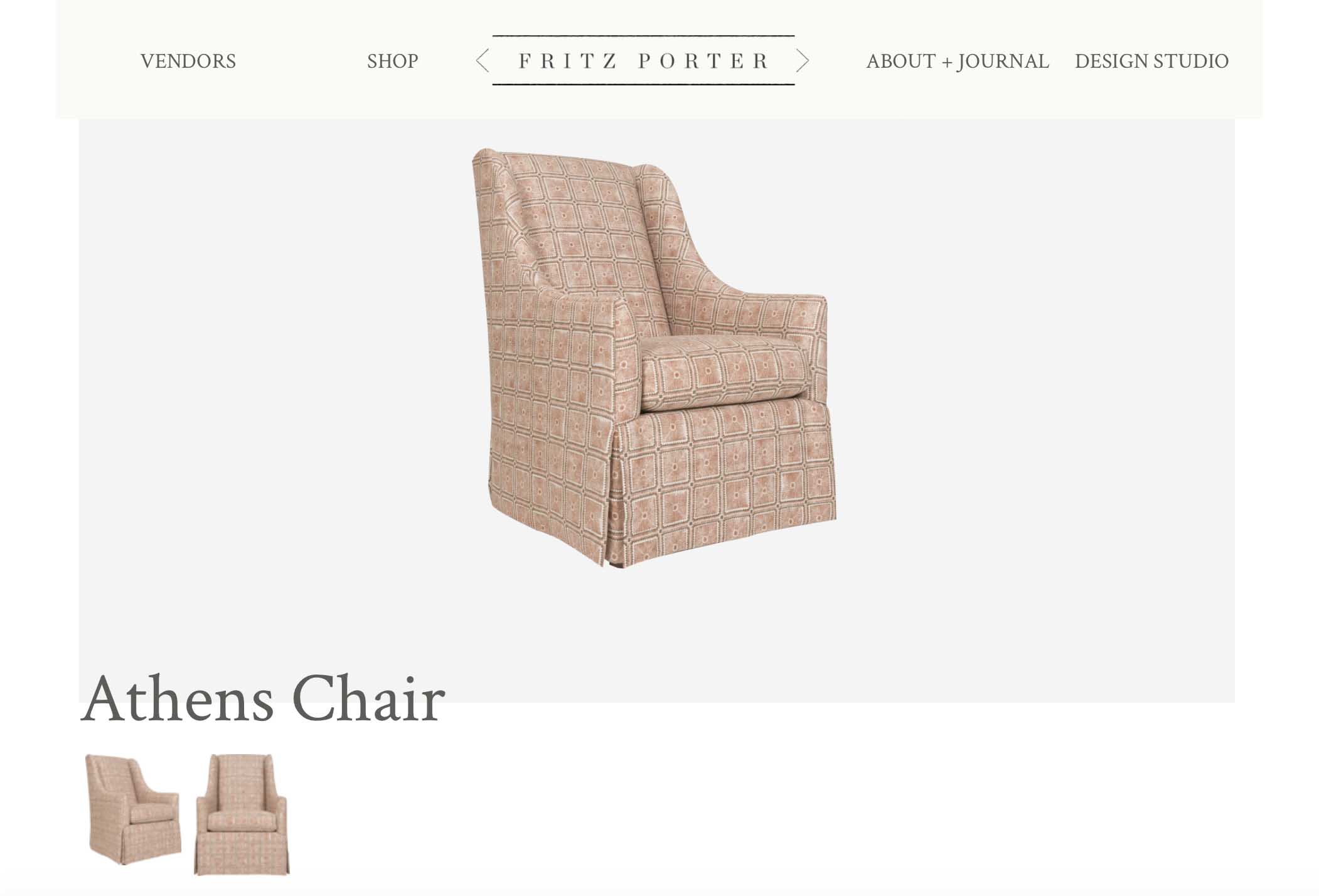

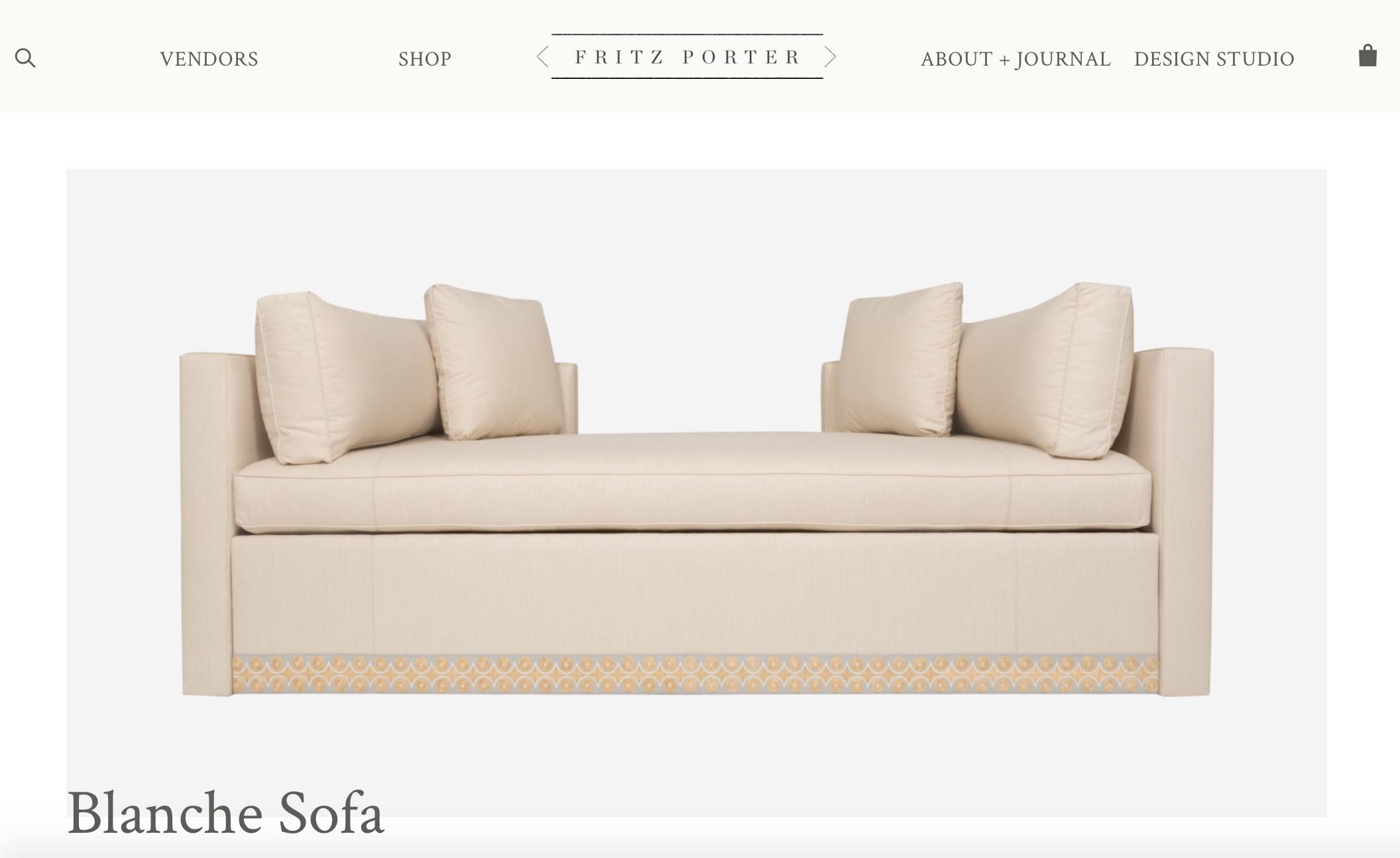

But something bigger than food is reshaping Charleston. There is more traffic, for one thing, but there is also an energy coursing through the city that reminds me of Nashville and San Francisco. Charleston is home to more than 250 tech companies now. Hip design shops are opening, like Fritz Porter Design Collective, where you can browse antiques selected by the South's best tastemakers. New events are crowding the calendar, like High Water Festival, "a celebration of music, food, and libations" from local artists Shovels & Rope. And the cocktail culture is keeping the city lubricated, from the tiki-themed South Seas Oasis, where you can sip mai tais in a space lined with bamboo and hula skirts, to the intimate, old-school Proof, celebrated for its crisp gin and tonic. On a Friday night, Upper King feels a little bit like a block party in Brooklyn, as people spill out of the bars, clubs, and restaurants. What not so long ago was a sleepy little town in the Lowcountry is becoming a city that never sleeps.

There is no better reflection of this changing city than the Dewberry Charleston hotel in a 1964 federal office building. I used to drop my kids off for preschool at the Presbyterian church across the street, and I barely noticed the monolithic Midcentury Modern structure that loomed over Marion Square. For years, cranky residents wanted it replaced with something more traditional. But in the eyes of former Georgia Tech quarterback and real estate magnate John Dewberry, it was a thing of beauty. "Most people wanted me to tear it down," he told me over coffee one morning in the lobby, which began welcoming guests two years ago. "But while a lot of people couldn't see it, a few of us could." Dewberry softened the building's façade with 35-year-old crepe myrtles, espaliered red maples, a walled garden, and gorgeous outdoor lighting that accentuates its vertical lines. More than any other hotel in town, the Dewberry is unapologetically modern, with Midcentury furniture that Dewberry and his wife, Jaimie, have curated from auctions all over Europe. The brass bar in the lobby (which they call "The Living Room") is the heartbeat of the hotel, always staffed by bartenders in white jackets who make a mean Old-Fashioned. If there's a better-looking bar anywhere in the South, I haven't seen it.

About a mile up the peninsula, the five-room 86 Cannon, the Poinsette House captures another side of the new Charleston. Modeled after other intimate properties in town, like Zero George and the Wentworth Mansion, the year-old hotel is set in a house dating from 1862. You can hear the wood floors creak under your feet on the piazza (pee-ah-za, as they say here), but everything about the experience is luxurious, from the décor to the sheets to the sleek Linus bikes that wait for you outside. Five years ago, the neighborhood was known for its sagging porches and rowdy college students who came for the cheap housing. Tourists had no reason to venture there, but now this tiny hotel is a destination for travelers from all over the world. When I asked the proprietors, Marion and Lori Hawkins, what these international visitors want to do, Lori answered without hesitation, "Eat."

"Something bigger than food is reshaping Charleston. There’s an energy coursing through the city that reminds me of Nashville and San Francisco."

It's a five-to-10-minute walk to some of the best restaurants in town, from Xiao Bao Biscuit, which serves inspired Asian dishes in a converted gas station, to Leon's Oyster Shop, where the fried chicken rivals any in the South. Or you can go for barbecue. Southerners have long nurtured a debate over whether Carolina-style pork or Texas-style brisket is the true king. Charleston has decided you can have it both ways. On Upper King Street, one year ago, Rodney Scott opened Rodney Scott's BBQ, a brick temple to the low, slow, whole-hog style that put South Carolina barbecue on the map. Less than half a mile away, at Lewis Barbecue, you can sit in a gravel courtyard under the shade of a live oak and enjoy some of the best brisket in the country, Texas-style. Like all real Texas barbecue, it's smoked for 18 hours and served on butcher paper with a couple of slices of white bread. You simply couldn't find brisket of this quality anywhere outside of the Lone Star State until the young, bearded pit master John Lewis decided to pack up his smokers and move here from Austin. What makes Lewis's even more interesting is that it sits in the emerging development of Half Mile North (a half-mile north of the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge), with its contemporary architecture, car-charging stations, and cluster of tech companies. This is where another revolution has begun, driven by a wave of start-ups, like the e-commerce firm Blue Acorn, that have helped earn Charleston the moniker Silicon Harbor. At Butcher & Bee, Web developers and digital entrepreneurs talk tech over shakshuka and brown-rice bowls. Edmund's Oast has become an evening hangout, with sophisticated dishes like chicken-liver parfait and exceptional craft beers.

Still farther up the peninsula, at the Pacific Box & Crate office complex, there are no porches in sight — just chic industrial buildings with soaring windows. Inside couldn't be more modern, with Ping-Pong tables, a yoga studio, and dogs lounging among the workstations. Stephen Zoukis, the real estate mogul behind the complex, recognized that Charleston needed a home for these new businesses — as well as another culinary center. "For a lot of these young people, having an alternative to downtown is important," he told me one morning at Bad Wolf Coffee, the campus caffeine hub. And so Zoukis launched Workshop, a food court showcasing all kinds of global cuisine.

I only lived in Charleston for about four years, but every time I go back, I feel the city's magnetic pull. It's not the quiet Lowcountry town I first fell in love with, but underneath all these new places, the character and charm of the city are still there. Ten years after that memorable dinner at McCrady's, Sean Brock is busier than ever, now overseeing eight restaurants in five cities, including new iterations of Husk in Greenville, South Carolina, and Savannah, Georgia. But McCrady's is where the chef is at his most creative. "That's my sanctuary," he told me recently.

A year and a half ago, he reimagined the restaurant as a 22-seat tasting-menu-only space, curating everything from the music to the silverware. McCrady's now serves 15 wildly inventive courses, such as a single Virginia oyster perched on a bed of smooth rocks with a cloud of steam rising from the bowl. I don't know what this portends for the next 10 years in Charleston, but I do take comfort in the fact that Brock is reinventing himself and his signature restaurant every day, just waiting for the next couple to come in and taste something out of this world.